Back to the requirements of FAR 52.245-1

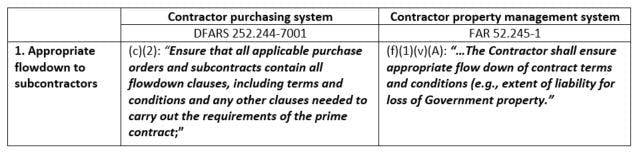

Let’s go back to the beginning of our discussion with FAR 52.245-1(b)(3) stating that the contractor shall “… include the requirements of this clause in all subcontracts under which Government property is acquired or furnished for subcontract performance.” The FAR 52.245-1 clause itself is a performance-based requirement, describing what needs to be done and not how to do it. It prescribes outcomes and outputs of a contractor’s property management system. That property management system depends upon the nature of the contractor’s business, the type and quantity of property, and the risks involved, a subset of which would be the surveillance of the subcontractor’s system. To the extent the prime contractor identifies a supplier as a subcontractor, the type and scope of assessment and surveillance is a prime contractor, not a government, decision, since the government has no privity with lower-tier suppliers. This language reflects the need to balance the government’s requirements for consistency through the contracting/supply chain (what needs to be done) while offering the prime contractor discretion on how to do it.

Contractors, like the government, must consider other factors, including commercial practices, supplier risk, cost, schedule and performance criteria. These may be acceptable depending upon the circumstances properly disclosed in the prime contractor’s disclosure statement, subcontracting plan or accounting or purchasing procedure; contractors need some degree of discretion on actual flow-down practice, for contractors must be able to navigate their business relationships with suppliers.

There has been anecdotal evidence of contractors receiving questions and even corrective action requests related to disagreements by the government over what a subcontractor is. Some of these disagreements revolved around the contractor’s alternate sites or divisions and even some around flowing down requirements to vendors. These disagreements often stem from another part of the clause:

"The Contractor’s responsibility extends from the initial acquisition and receipt of property, through stewardship, custody, and use until formally relieved of responsibility by authorized means, including delivery, consumption, expending, sale (as surplus property), or other disposition, or via a completed investigation, evaluation, and final determination for lost property. This requirement applies to all Government property under the Contractor’s accountability, stewardship, possession or control, including its vendors or subcontractors (see paragraph (f)(1)(v) of this clause).”

This language clearly distinguishes between vendor or subcontractors since only the subcontractor portion gets its own requirements at FAR 52.245-1 (f)(1)(v). In other words, FAR 52.245-1(f)(1)(v) does not apply vendors, only subcontractors.

The above underlined portion is an extension of the contractor’s stewardship responsibility to state that “you the contractor are responsible for property at the vendor or subcontractor, but with subcontractors you have additional responsibility.” One could argue that some sort of surveillance of property with vendors is required. This could include requiring them to be insured or otherwise meet some sort of professional standard. But clearly, vendors are generally subject to different terms and conditions, especially if they are commercial entities.

FAR Part 45, the part of the FAR that prescribes the government’s actions related to government property as well as the source of the prescription of FAR 52.245-1, states:

“Agencies will not generally require contractors to establish property management systems that are separate from a contractor’s established procedures, practices, and systems used to account for and manage contractor-owned property.”

This government policy stance, often overlooked, clearly supports the view that contractors should not be required to do something different. The question is who is in a better position to identify a subcontractor: the government or the contractor?

A would-be government prescription to a contractor about its definition or identification of subcontractor in essence “breaks” several things. First off, it goes against the prohibition in FAR Part 45 of requiring contractors to do things differently. Second, it can cause direct conflict with a contractor’s purchasing procedures and, in cases of contractors with approved purchasing systems, upend the government’s own approval of the system that includes procedures for the contractor to identify and define subcontractors. Third, the government risks forcing a CAS noncompliance by prescribing different or special definitions for subcontractors in different circumstances. Contractors with CAS-covered contracts are required to treat all costs incurred for the same purpose, in like circumstances, consistently, [9] which the government would already have reviewed and audited as both part of the CAS disclosure statement and any related accounting system audit and system approval.

Ultimately, contractors should take a position within their policies and procedures considering what is reasonable and consistent given their business environment, type of government property, cost accounting practices, procurement practices, and any other business system or regulatory dependencies and interdependencies that may be applicable in order to ensure that they appropriately flow down contractual requirements.

For more information on this article or to understand how we can help, contact our team.