Supply chain resilience: exploring nearshoring to unlock new frontiers of strength

The trade war dispute between China and the U.S. prior to 2020 instilled uncertainty and mixed messages of the benefits of a global economy. Companies were cautiously considering nearshoring as a solution. Then the COVID-19 pandemic arrived, causing great disruption in many companies’ supply chains and leaving them with idled plant floors, empty warehouses and unsatisfied customers. Because of this disruption, companies have a greater incentive to consider nearshoring some or all of their key supplies.

For context, nearshoring refers to an organization’s transfer of certain business operations, in particular its own manufacturing capability or a key supplier, to a nearby country closer to the demand location for its manufactured products. For U.S. companies, nearshoring may mean moving a supplier from China, one of the U.S.’ top trading partners, to Mexico or Canada, the U.S.’ other two largest trading partners. Additionally, in considering a move from Asia, some manufacturers with European presence often evaluate select countries in Eastern Europe, such as Poland and Slovakia, which provide analogous benefits for companies with a European manufacturing footprint.

Initial consideration filter: labor- vs. capital-intensive products

While the suitability of nearshoring is highly specific to an individual company and its products, there is one initial and reliable filter employed towards determining whether such a strategic decision holds further exploration: labor content. Specifically, whether a company’s products and its value-add capabilities rely on a greater proportion of manual labor versus automation in the production of its goods.

Regional consumption potential and market size opportunity aside, Asia-based operations and supply base expansions saw their rise early on due to a strong connection with abundant labor supply, low wage rates and increasingly greater production capability.

Fast forward 20 or so years to today, when the productive workforce in such low cost countries achieved greater prosperity. The result: labor cost inflation and a growing purchasing power of the populous combine with logistic challenges and the rise of a trade war across key world economies. Suddenly, for companies whose products rely on intensive labor input, the total landed cost of manufactured or purchased goods from low labor wage countries begin to lose their appeal.

Organizations with “capital-intensive” products are also looking to nearshore their supply chain in the wake of the pandemic. Capital-intensive products require high-precision machine operations and automation, with a comparatively lower manual labor content. Examples would be manufacturing an automobile’s drive train and steering system. The serious supply chain disruption of 2020 makes the decision to rely on a supplier in a low-wage, distant country suddenly look like an expensive proposition. Thus, nearshoring manufacturing of these types of products becomes particularly attractive, even when moving this manufacturing may be difficult and expensive in the short term.

A June 2020 survey from Gartner of 260 global supply chain leaders found 33% had moved sourcing and manufacturing activities out of China or plan to do so in the next two to three years. Other sources indicate a double-digit decline in U.S. imports of manufactured goods from China from 2018 to 2019 – in no small measure due to the trade tensions between the two countries. The result: an offset in imports from other countries and the acceleration of nearshoring supply to the Americas.

For instance, in the same period, U.S. manufacturing imports from other low-cost Asian countries increased by $31 billion, while imports from Mexico increased by $13 billion. In essence, while the trend toward nearshoring had begun prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the pandemic exacerbated the effect of China-centric tariffs, creating an accelerant for companies to consider nearshoring their operations and suppliers when possible and feasible.

China and other Asian countries do not make the decision to nearshore an easy one, especially for products that require substantial transformation and value-added labor. China in particular has the workforce, equipment, economic system and currency that gives them an advantage over many other countries vying for sourcing preference. Beyond manufactured items, China retains the source of many raw materials incorporated into a number of essential industrialized goods. Intentional or not, this is a strategic position (if not an advantage) for China that frequently poses challenges for mature supply chains in need of change but also dependent on such factors.

Logistical challenges

Labor and materials constitute one of many input variables to manufactured goods. Once made, they have to be transported – and the variables to be considered are many, including:

- Physical establishment of buildings, processes, people and technology

- Cost of moving, including movers, replacing broken items and prepping the new space

- Transition cost, including possible down time and supply interruptions during the move

- Logistics of establishing new shipping lanes and distribution channels from the new supplier

- Possible investment tax credits offered by the jurisdiction of the new supplier

One of the most direct benefits of nearshoring is its positive impact in a company’s working capital. Specifically, by reducing the shipment lead-times and related inventory in transit, the total ‘hold time’ for cash outlay to suppliers and receipt from customers, makes it such that working capital ‘float time’ is often reduced to days – instead of the typical six to eight weeks of transit time between China and the U.S. Increased working capital strengthens the balance sheet, provides reduced dependency on credit facilities, and directly contributes to the organization’s financial health – to name a few.

Factoring in both the logistical costs of moving product and the cost of capital provides a company with meaningful perspective and confidence in its decision to keep production / sourcing stay in China or another Asian country, or to nearshore.

Nearshoring considerations

Data-driven viability assessments are an important piece of any near-shoring pre-deployment evaluation. When considering the challenges of near-shoring, forward-thinking manufacturers consider a wide range of variables, some of which include:

- Freight and insurance costs: The long spans of ocean separating Asian supply locations from the Americas come with a comparatively high cost of shipping and insurance relative to a near-shore location like Mexico. Not surprisingly, the cost of shipping from China has fluctuated in 2020 due to the pandemic. According to Hellenic Shipping News, in October, shipping costs from China to the U.S. West Coast were 30% higher than the same period in 2019; costs to the East Coast almost doubled.

- Lead times: By bringing their supplies closer to the demand points for their products, companies reduce long lead times, among other benefits. Doing so enables a company’s products to reach the end customer faster – which also has a direct impact in working capital (shorter hold times and lower inventory needs), customer satisfaction and competitive market performance, to name a few. These benefits are in the times of “normal course of doing business,” and do not factor in the impact of disparate time zones, significant language gaps and culture alignment differences that become even harder to manage during a global pandemic.

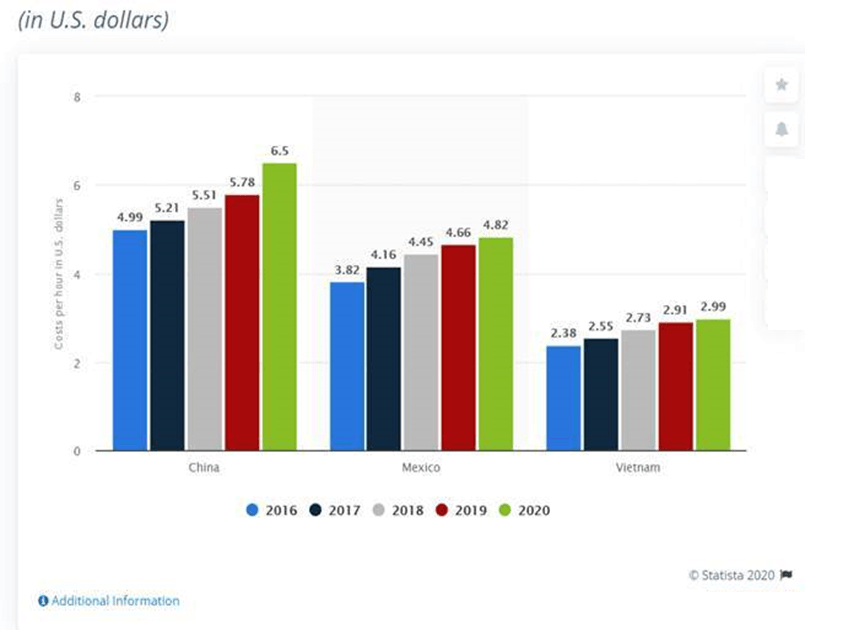

- Labor costs: The difference in labor costs between Mexico and China has become clearer in recent years. Mexico labor rates have remained effectively flat. According to Statista, from 2019 to 2020, manufacturing labor costs per hour for China increased from $5.78 to $6.50 USD, while Mexico experienced a much smaller increase from $4.66 to $4.82 USD over the same time period. Couple this with rising labor cost and overall inflation in China, and the case for relocating manufacturing labor to the Americas can be compelling.

Manufacturing labor costs comparison – China and Mexico

- Labor availability: Mexico, along with some Eastern European countries, have highly experienced labor forces that are adaptable to different types of manufacturing. While most industrialized areas in manufacturing-centric regions come with competition for qualified labor, the emergence of industrial parks in locations adjacent to such high-demand regions provide access to a growing labor pool at competitive local rates.

- Stability in tariff regime and trade relations: The U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), the end result of negotiations from two distinct administrations and their resulting policies (Barack Obama and Donald Trump), foster an environment for trade relations between Mexico and Canada that is far more stable than those with China and other countries. This favors near-term and long-term planning considerations of Mexico as a manufacturing and import/export hub for the manufacturing sector’s leading performers.

- Mirroring: Larger organizations are also looking to create “mirrors” or redundant supply sources in two or more locations to create resiliency within their supply chain. This may mean a company will have similar suppliers in China and a nearshore country, balancing capacity between both locations. As the business grows, supply volumes grow in both locations. If one location is shut down by a natural disaster or pandemic-like event, the company can more easily shift operations to the unaffected country’s supplier.

Organizations ranging from consumer product companies to heavy motor equipment suppliers realize they are exposed to risk in their supply chain in ways that could make it difficult to operate profitably or even shut down the business. Investigating alternatives, which will require comparing all of these variables in more than one country, typically require a company to seek outside assistance to make a smart decision. One way companies can investigate if nearshoring will help bolster supply chain resiliency is through a “battle drill.”

Conducting a battle drill

Technical capability, historically low wage rates, available labor pool, existing supply of capital equipment and inputs, attractive export/import tariff structure, and favorable currency exchange rates are just a few of the compelling factors that, until recently, had made China and other Asian countries among the most attractive manufacturing destinations in the world. These factors, coupled to prosperity at home (particularly in the U.S.), contributed to nearshoring being of little interest to many U.S.-based manufacturers.

It is no wonder, then, that it would take a scenario of tariffs-meet-pandemic for manufacturers to undergo supply chain pressures significant enough to warrant nearshoring consideration. Yet, consideration alone is not sufficient to build a resilient supply chain that can withstand such headwinds, and organizations that survived the recent disruption in supply chain recognize the need to prepare for the next round of similar disruption.

One way to prepare is to conduct a battle drill. In essence, this entails a simulation exercise by which a company undergoes the scenario planning, feasibility study, cost estimation and nearly every pre-deployment action except actually nearshoring the target operation or supplier.

A complete battle drill would include dynamic scenario modeling, deep analytics on material movement and total applied cost, new facility simulation, inventory buffer build, facility decommissioning and re-start cost determination. A good battle drill includes a preliminary work plan to implement the nearshoring effort, which further crystalizes the timing, resources and dependency requirements. The output of such an exercise is a confident decision on whether to nearshore and, if so, the specific economic, tactical and strategic benefits in doing so. Together, these items provide the necessary detail for subsequent steps, including internal organizational alignment/change management, budgeting and possibly external debt to finance such operations’ relocation.

For supplier-related nearshoring, this battle drill includes selecting the most likely inputs and/or items to be sourced in the Americas, producing the necessary drawings and specifications, researching and qualifying potential vendors, and conducting a multivendor bid process. Coupled with analysis in capacity planning, freight, insurance, transit time and tariffs, this exercise places a company in sure footing to determine whether a supply base should be relocated to closer shores, as well as where and to whom.

The battle drill exercise can largely be outsourced to a capable provider to accelerate execution, improve outcomes and reduce the overall investment in reaching a “go”/“no go” decision to nearshore.

Given its high degree of specificity, this battle drill approach significantly increases the confidence and speed required to inject resilience in one’s supply chain, while yielding the necessary quantitative and qualitative detail for potential next steps should it yield a “go” decision to nearshore.

Nearshoring as a transformative organizational catalyst

Irrespective of geopolitical or socioeconomic shifts – and their effects on trade relations and economic policy – critical supplies that rely heavily on remote sources are more vulnerable to disruption than those near their consumption point. A disruption such as a global pandemic can make minor distance vulnerabilities swell to a crippling effect on a company’s supply chain. The current public health crisis that has decimated a number of companies with fragile supply chains stands as proof.

The current COVID-19 crisis is unlikely to be an isolated event in coming years. This prospect of a pandemic-laden world calls for sound leadership decisions and the prudence of foresight, planning and action in the face of known and unknown variables. Companies owe it to themselves, to their team members and to their customers to investigate nearshoring as part of an instrumental variable in injecting resiliency into their supply chain.

Even if a company decides to keep its existing suppliers, and not to nearshore, the clarity that emerges from better understanding one’s own supply chain, its potential vulnerabilities and opportunities to materially improve speed, agility and working capital can have a profound effect on organizational strength.

And strength, pandemic or not, is invariably welcome.