GAO sounds the alarm on “urgent need” to improve supply chain security: what this means for federal contractors

On Dec. 15, 2020, the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report casting a spotlight on the inadequate management over supply chain security at all 23 civilian federal agencies audited – just days after news of the disturbing SolarWinds supply chain infiltration into federal networks began to emerge. Shared directly with congressional committees in October 2020, the report (GAO-21-171) – revised for public consumption due to sensitivity concerns – represents a critical call to action at a time of uncertainty as agencies grapple with the fallout from SolarWinds. Baker Tilly has summarized key findings from the report and provided its perspective on important takeaways for the government contractor community.

Report at a glance

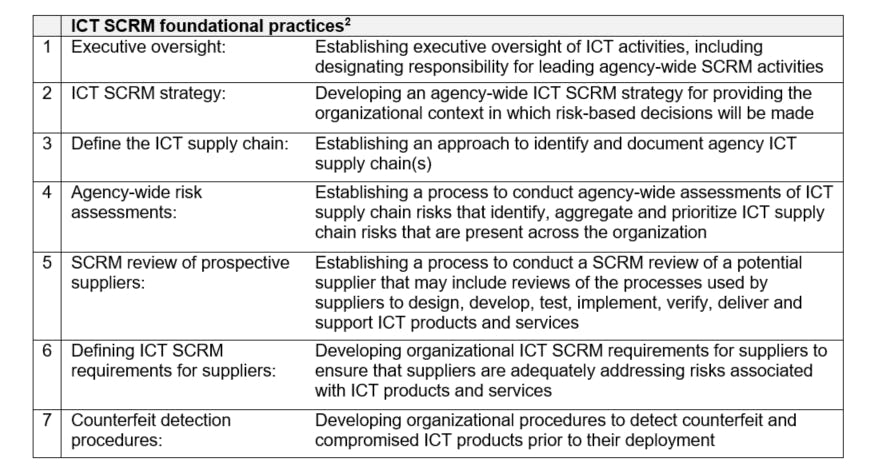

The federal government’s reliance on information and communications technology (ICT) has made the supply chain for these products and services a threat vector that poses a significant risk to national security. The GAO was tasked with examining the extent to which federal agencies have implemented seven foundational practices associated with an effective approach to organization-wide ICT supply chain risk management (SCRM). The foundational practices, which were identified by reviewing guidance from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST),[1] include:

Conducted from December 2018 through October 2020, the performance audit found significant deficiencies in properly managing supply chain security. As stated within the report:

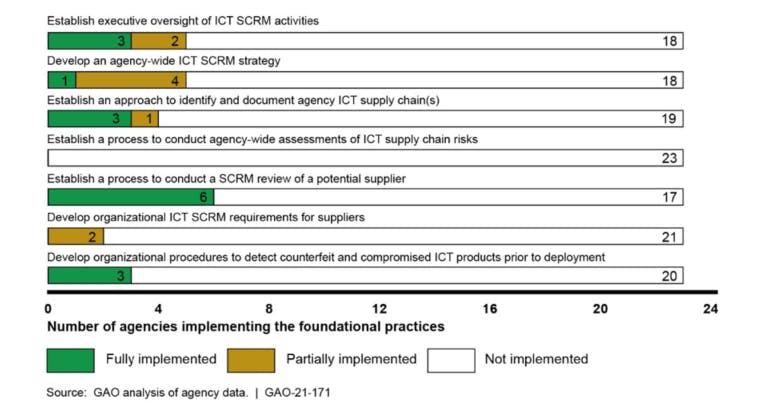

“Few of the 23 civilian CFO Act agencies had implemented the seven selected foundational practices for managing ICT supply chain risks. Further, none of the agencies had fully implemented all of the selected practices for managing such risks and 14 of the 23 agencies had not implemented any of the practices. The practice with the highest rate of implementation was implemented by only six agencies. Conversely, none of the other practices were implemented by more than three agencies. Moreover, one practice had not been implemented by any of the agencies.”

This poor performance is depicted in the following summary table, which appears in the report as “Figure 2: Extent to which the 23 civilian Chief Financial Officers Act agencies implemented ICT SCRM practices”:

According to the report, several agencies commented that a major reason why one or more of these practices had not been implemented was because they were waiting for federal SCRM guidance – primarily from the Federal Acquisition Security Council (FASC). While a variety of efforts from the FASC are underway, the report also noted that agencies were required by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to address their ICT supply chain risks in 2016. This is in addition to a variety of publications from NIST that agencies should be accessing to help manage their ICT supply chains.

Several other agencies reported that they couldn’t implement the processes due to having federated organizational structures. One agency’s chief information officer (CIO) had made a decision to not formally create a SCRM program, as the agency did not have enough systems that required them. Another agency stated that the office of the CIO did not establish a SCRM program “due to the complex nature of these efforts.”

Regardless, all of the audited agencies exhibited gaps in their ICT SCRM practices, which leaves them at greater risk for intrusion and/or exploitation. As stated succinctly within the report:

“Until agencies implement all of the foundational ICT SCRM practices, they will be limited in their ability to address supply chain risks across their organizations effectively. As a result, these agencies are at a greater risk that malicious actors could exploit vulnerabilities in the ICT supply chain. Securing the supply chain and the information it contains is essential to protecting key agency mission operations, including those related to energy, economic, transportation, communications, and financial services.”

Fortunately, after this report was issued, agencies have come forward to indicate that they are working diligently to enhance and/or implement these processes. For example, the Department of Education wrote a letter to the GAO stating it has been reviewing OMB guidance and is further developing their SCRM processes.

What this means for government contract community

The GAO recommendations re-emphasize that as supply chain ecosystems become more sophisticated, the SCRM practices implemented by the federal government must evolve with it. Enhancements in each agency’s SCRM security posture have the potential to impact federal contractors – as they service these entities – in several important ways:

- Increased scrutiny:

In the face of rising uncertainty over surveillance by foreign adversaries, federal contractors will likely be subject to increasing scrutiny over their supply chains. If these organizations wish to continue servicing agency customers, they should develop proactive measures to ascertain their own level of SCRM maturity. The foundational practices identified by the GAO are a good place to start. Interestingly, one of the foundational practices calls for a “SCRM review of potential suppliers.” According to the report, this review would entail:

“… reviews of the processes used by suppliers to design, develop, test, implement, verify, deliver, and support ICT products and services. In addition, the process may incorporate reviews to ensure that primary suppliers have security safeguards in place, including a practice for vetting subordinate suppliers (e.g., second- and third-tier suppliers, and any subcontractors).”

Federal contractors should be assessing if they are ready for a SCRM review should an agency customer decide to conduct one.

- Supporting efforts to define the supply chain:

A foundational practice identified by the GAO is that agencies should take steps to map their supply chains to the furthest extent possible:

“Federal agencies should establish an approach to identify and describe or depict information about their ICT supply chains that includes, as relevant, suppliers, manufacturing facilities, logistics providers, distribution centers, distributors, wholesalers, and other organizations involved in the manufacturing, operation, management, processing, design and development, handling, and delivery of products and services.”

The report indicated that only three agencies had fully implemented this practice (and 19 agencies had not). Interesting, of the three agencies, one had adopted a supply chain illumination tool to assist it in meeting this foundational practice. The tool:

“… leveraged artificial intelligence and an underlying algorithm to analyze, among other things, publicly available information about suppliers (company and product), including company summaries … [and] also provided real-time alerts for specific suppliers within the agency’s environment.”

As this finding demonstrates, technology can often be employed and serve as one component of many that will enable an organization to efficiently map its supply chain and identify changes and new risks as they arise. As agencies look to bolster their practices in this area, federal contractors may be called upon to support their customers in providing visibility into their ICT supply chains.

- Use of SCRM requirements:

Notably, supply chain security has begun to manifest itself in key acquisitions throughout the procurement landscape. The GAO identified a foundational practice that looks to advance these requirements to provide assurance as part of contract execution. All 23 agencies had not implemented this practice fully. As stated within the report:

“Without organizational ICT supply chain security requirements for inclusion in contracts, agencies lack an essential mechanism to ensure that suppliers (and their suppliers) are adequately addressing risks associated with ICT products and services.”

Again, as agencies strengthen their practices in this area, federal contractors should expect to see increased use of requirements to provide detailed plans of action to protect hardware, software and embedded components from compromise (otherwise known as a “SCRM Plan”). To avoid any unnecessary surprises within a targeted acquisition, federal contractors would be wise to consider how it might assess systems, policies and processes to allow it to better understand its supply chains and effectively mitigate and manage risks.

For more information on this and SCRM, or to learn how Baker Tilly specialists can help – please contact us.

[1] Specifically, the foundational practices were identified by reviewing NIST’s cybersecurity framework, NIST SP 800-161, NIST SP 800-37 (Revision 2), and NIST SP 800-39.

[1]Please see “Table 2: Selected Foundational Practices for Information and Communications Technology (ICT) Supply Chain Risk Management (SCRM)” in the report for detailed descriptions of each ICT SCRM practice.